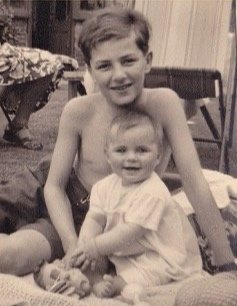

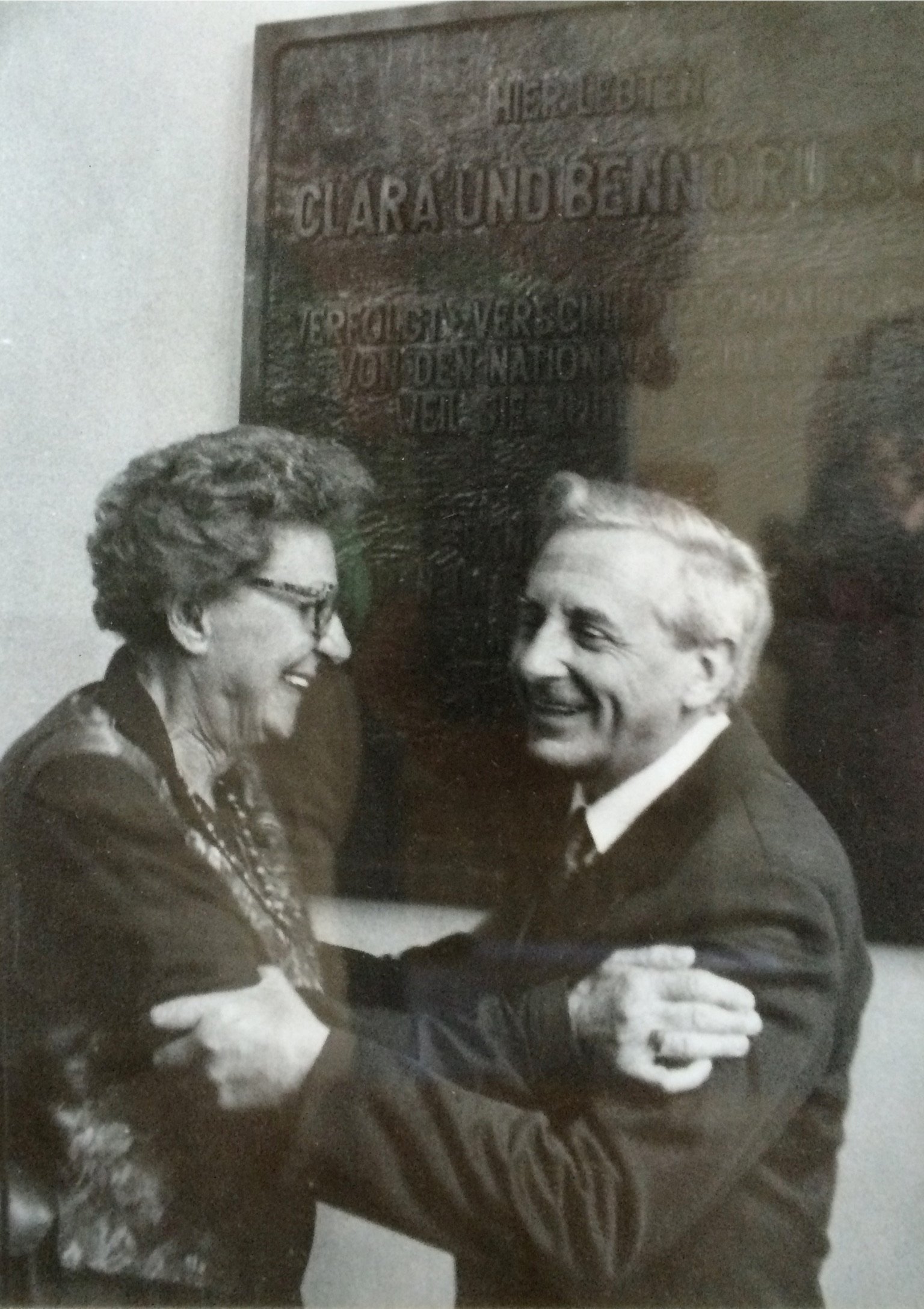

Julia and Michael Nelki, 1954

Alice Witte, née Nelki

Fenner Brockway

Bertha (Beate) Marcus, née Russo

Mathilde Russo

Isaak Russo

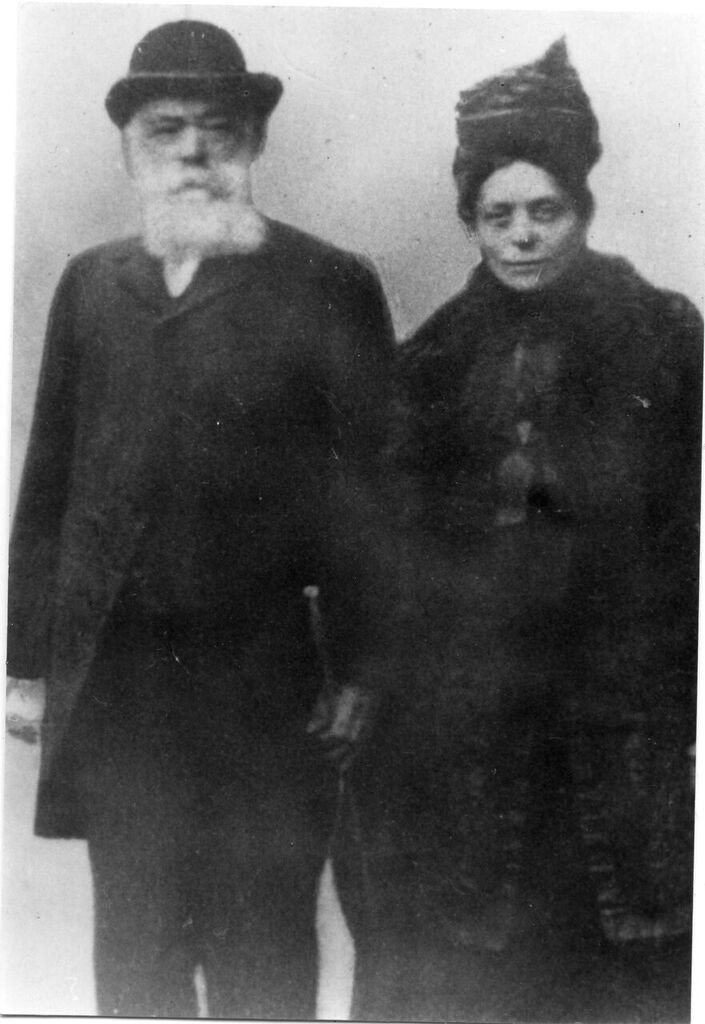

Jakob Julius & Dorothea (Koch)

Fritz Nelki with his dad Hermann - WW1

Ernestine with her youngest child, Wolf, my dad

Jakob Julius Nelki

Louis Nelky, my great great grandad

Erna Nelki, 1930, my mum, aged 16

Benno Russo

Karl & Moritz Russo

Fritz Nelki

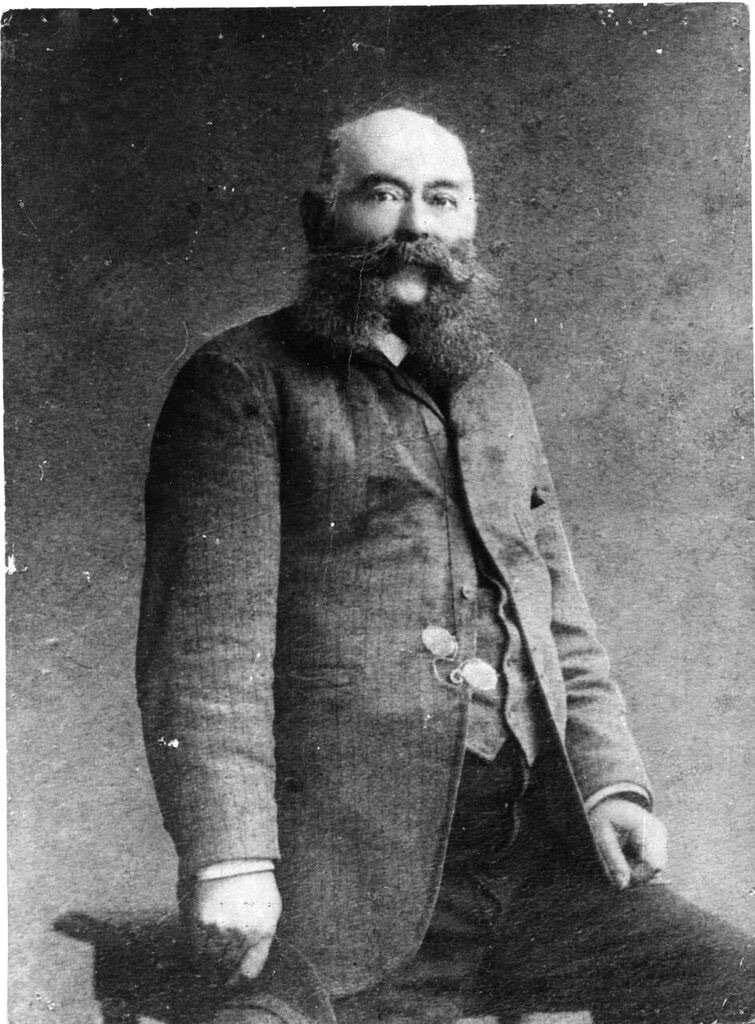

Hermann Nelki

Clara & Benno Russo in 1936

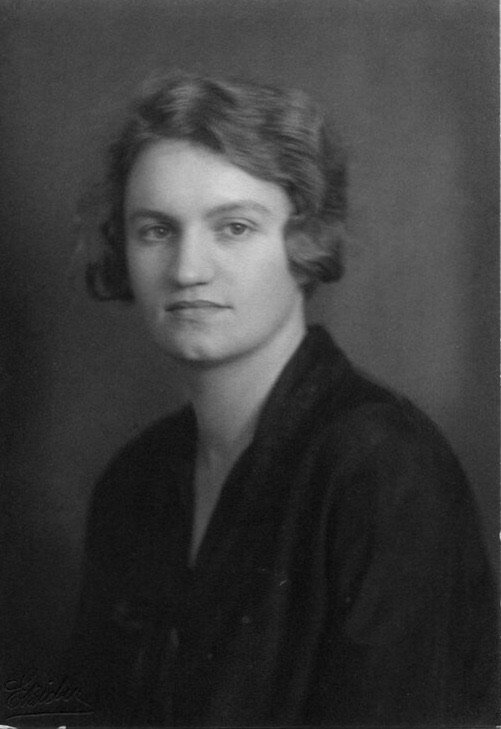

Alice Nelki, my aunt

Lina née Halibut

Jaques Russo

Grete Swede, née Russo

The children of Moritz & Marie Russo

Elisabeth Russo

Otto Nelki

The Hungarian Nelkys

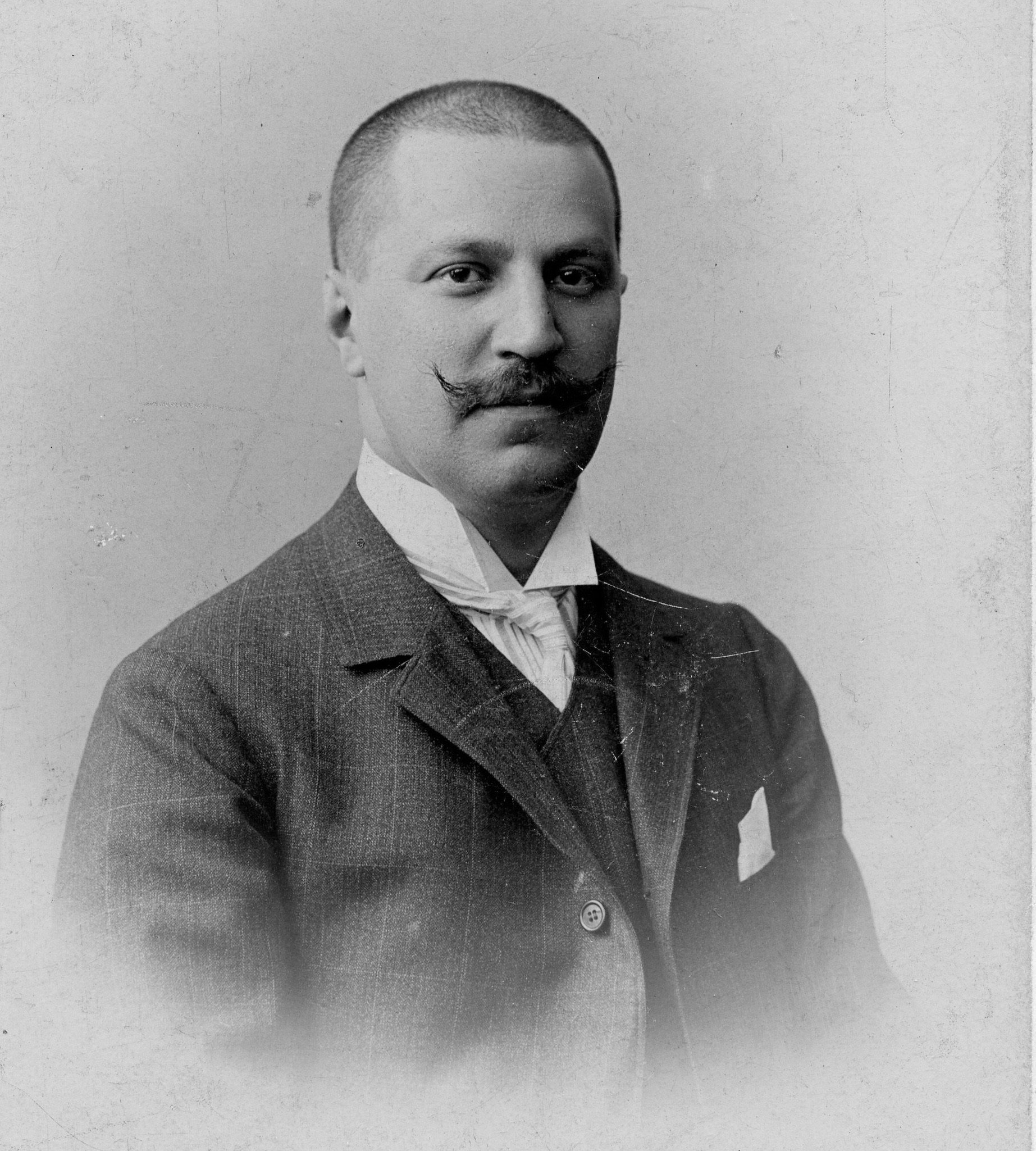

Benno Russo, 1904

Ernestine & Hermann Nelki on their wedding day 1890

Clara Russo, née Jaffe

Erna Nelki with Ziomek in Wernigerode, 1995

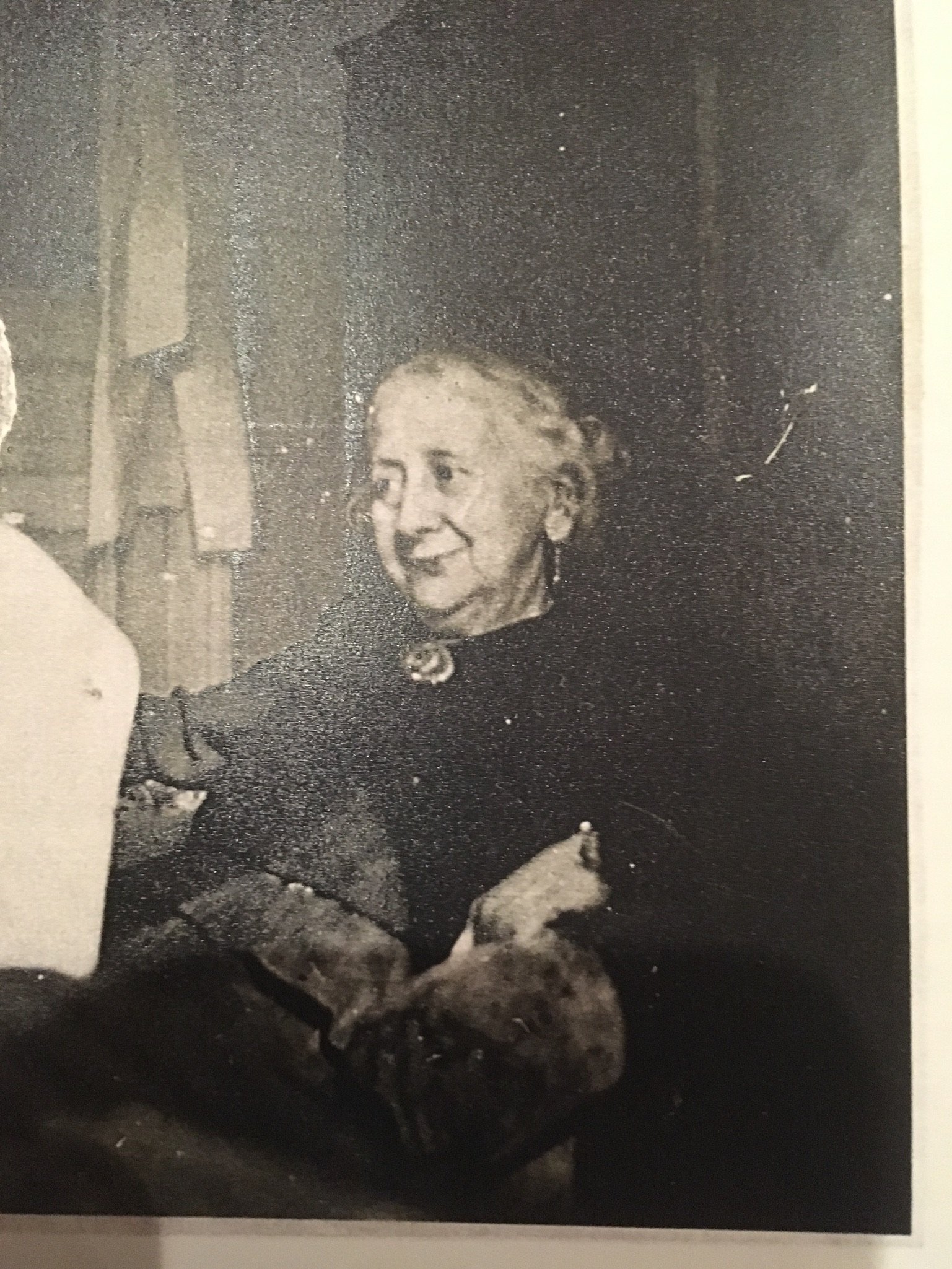

Ernestine Russo, age 19

Lilo Hardel

Prof Nati Steinberger

Max Nelki, 1939

Josef Nelky, Hungary

Alice Nelki, killed in Riga

Edith (née Nelki) & Siegfried Schmulewitz, murdered in Auschwitz

Fritz - left with friend

Gabi, Otto's wife

Otto Nelki

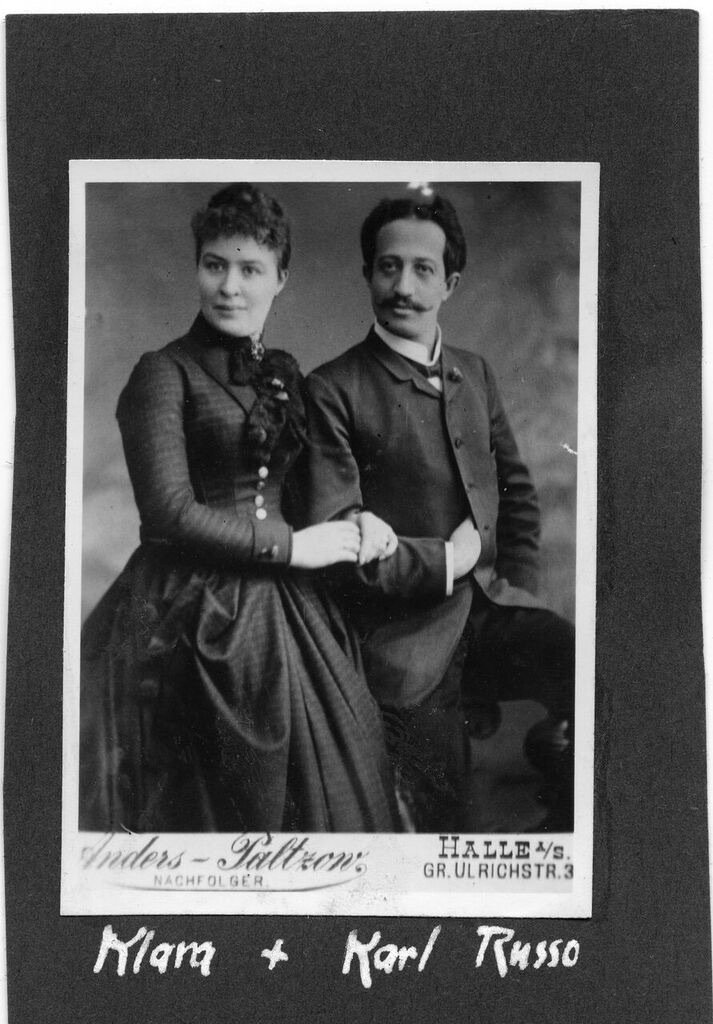

Klara & Karl Russo

Leopold, Sara & their household

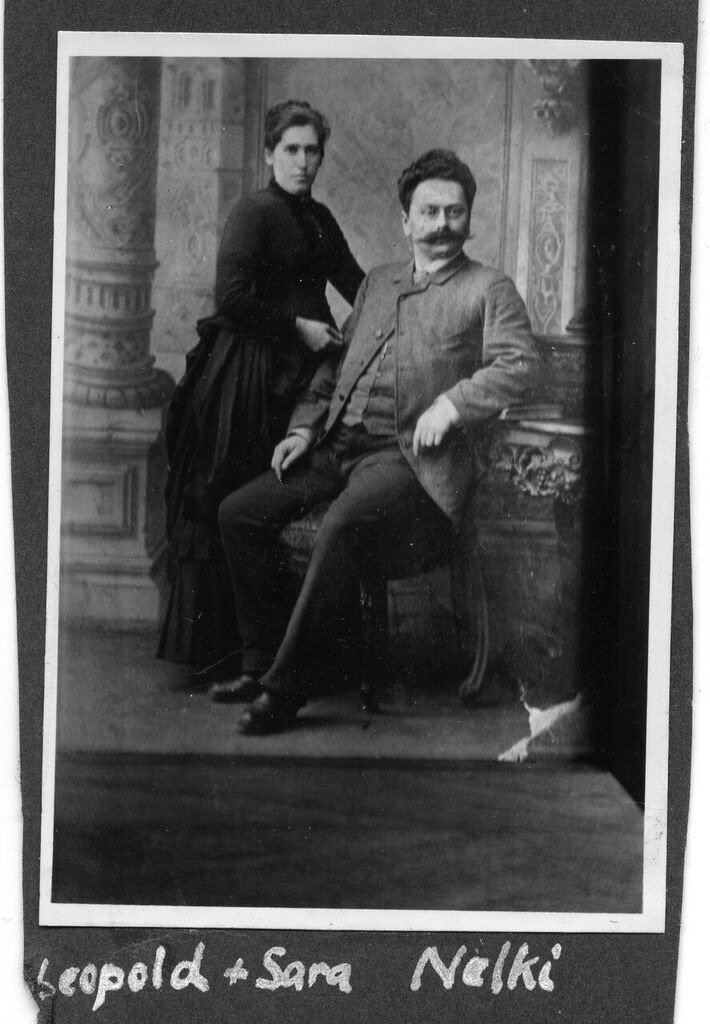

Leopold & Sara Nelki

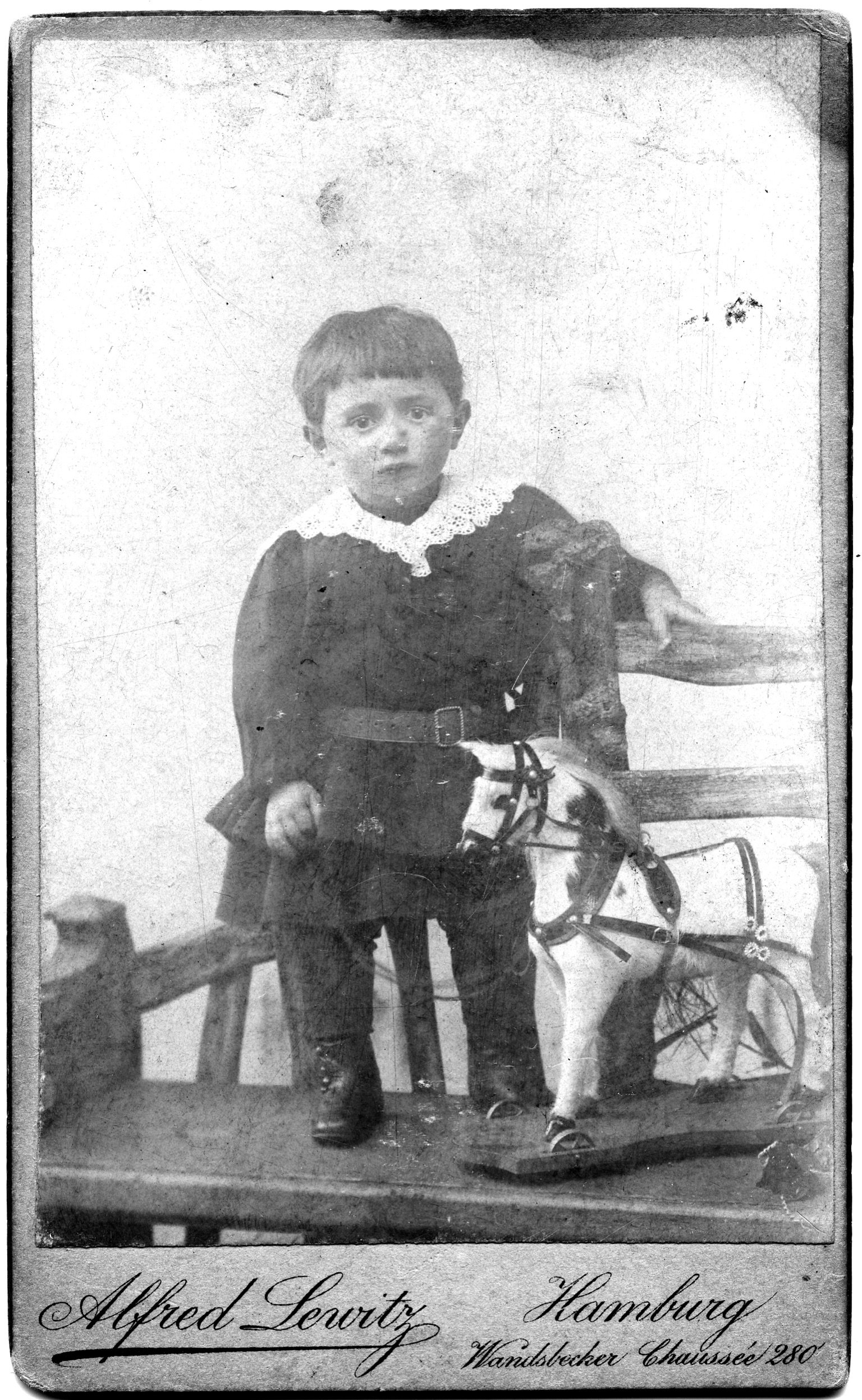

Otto, aged 2

Wolf

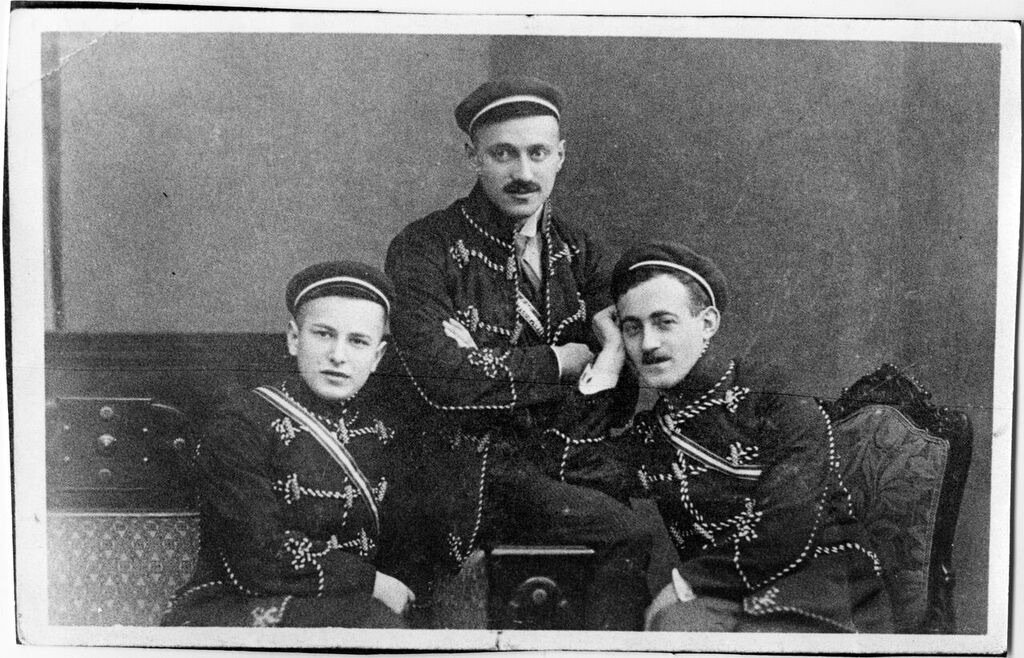

Fritz - centre

Ilse (Wolf's sister who died aged 10 in 1917) with Hedwig, her nanny

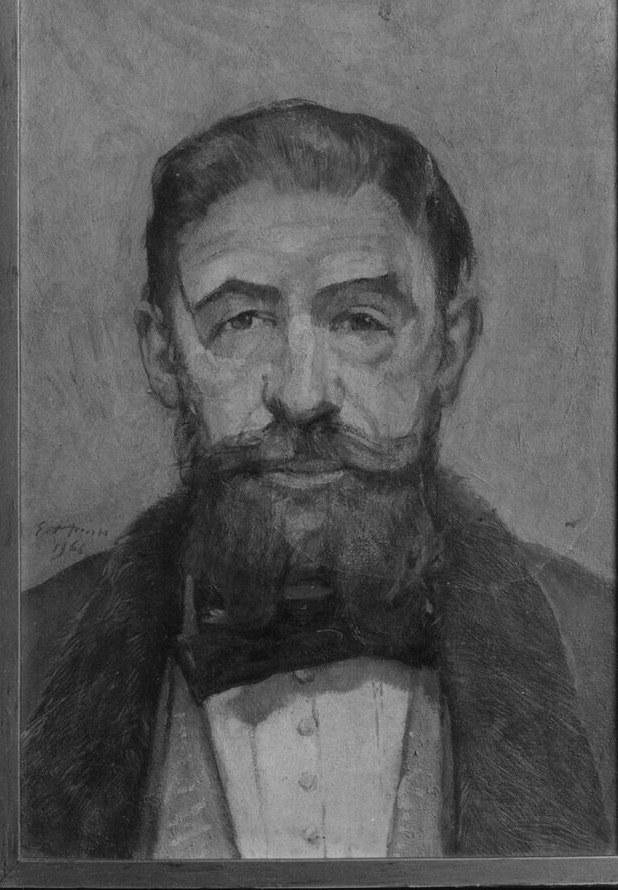

Otto interned in Hutton, drawn by Eugen Hirsch

Ilse (Wolf's sister who died aged 10 in 1917)

Hans, Wolf's brother who died aged 3 of scarlet fever

This website is dedicated to archiving my father’s research about the family Nelki, and ensuring that my book Villa Russo: A Jewish Story (Villa Russo: Eine Deutsche Geschichte) is accessible.

Villa Russo

By Julia Nelki

My book, Villa Russo, brings together my father’s work on the family’s past and how our family was affected by the Holocaust. It centres on a Villa in former East Germany and our ongoing connection with the family who live there now. The link with, and support for communist East Germany and socialist ideas that survived in spite of how they had been interpreted, is a perspective often not told.

Villa Russo and other publications relating to the family can be purchased here.

Containing photographs, personal documents, newspaper articles and other media relating to the Nelki family.

Also an expanding section on Stolpersteine as the work grows.

Many of the Nelki photographs are interesting in themselves as a reflection of the times they were taken (many in the 19th/20th centuries).

Some have been restored by Andra Nelki.

Message from author Julia Nelki

Creator of the Nelki family website and author of Villa Russo.

Contact Julia here.

I’m glad you’ve found my website. Perhaps you stumbled across it. Stumbling stones – ‘stolpersteine’ – are powerful physical memorials to the Jews who were killed in the Holocaust or who had to flee. They are brass plaques set into the pavement in front of the last home the victims lived in before they were forced to leave. There are many for members of my family.

The family trees that I have created focus on my father’s side because that’s where most of the stories come from. They represent only a tiny portion of my family and other branches have their own tales to tell. Our origins are Ashkenazi (Jews from Germany and Eastern Europe) on one side, and Sephardic (Jews from Portugal and Spain) centuries ago on the other.

My parents, Erna (née Liesegang) and Wolf Nelki who was Jewish, were both political refugees from Berlin in the 1930s. They were idealists and as young adults they lived through an important period of history when socialism seemed a real possibility. Instead, their dreams of a fairer society were cruelly shattered by the rise of Nazi fascism after 1933. Barbarism took over, an organised, state-controlled barbarism such as had never been seen before. Many of my parents’ friends, as well as members of my dad’s family, were killed. Others became refugees.

As a result of the Second World War, my father started researching what had happened to all these people and in the process he traced his family back many generations, uncovering the effects on them, and on other Jews, of long-standing anti-Semitism. He became particularly interested in how poor Jews had survived when they had no civil rights or permission to work.

What shocked me was how, even after the war and after the collapse of communism in the East, the stories of what happened to Jews were covered up, suppressed. Perhaps it isn’t surprising. It must be hard for people, and whole communities, to face up to what they, or their parents’ generation, had allowed to happen.

And it’s still happening today: people seeking asylum, refugees and outsiders are often excluded, stigmatised and persecuted rather than welcomed, and the stories of their sufferings go untold, ignored or deliberately concealed.